|

|

||||||

![]()

IN the autumn of 1877, shortly after the momentous interview alluded to in the last chapter, behold me, passed by the great author, rehearsing the part of Doctor Daly at the old Opera Comique theatre, now only a memory. My first appearance in London in a musical piece, and its title The Sorcerer — and what a prophetic title too, except that it should have been in the plural, for indeed two sorcerers had arisen to bewitch the ears of the public. And now think of this, some of ye modern actors who own motor-cars and palaces in Park Lane or Pimlico, I made the initial success of my career in one of the most important parts in a comic opera for the stupendous stipend of six pounds per week. Moreover, having made the success, I did not immediately clamour for better terms, and equally strange to relate, the management did not offer them. I do not wish for a moment to imply that I was more exceptionally cheap than the other artists of the company, which included my dear old colleague George Grossmith, jun. (as he was then); Bentham, a tenor who came, I believe, from Covent Garden opera; Richard Temple, Alice May, Giulia Warwick, Fred Clifton, and, as I have said, Mrs. Howard Paul. I have a shrewd suspicion that the all-round average would not have run to much over double figures. What halcyon days for managements! and who can wonder at the fortunes amassed, and justly, by the great triumvirate? for after all they took a certain risk in letting loose on London a band of artists some of whom had never before been heard of.

For the matter of that, none knew very much about Gilbert and Sullivan except for the wonderful success of their cantata, Trial by Jury, which had shortly before this amazed and delighted London with the brilliancy and humour of both words and music, although even then it was impossible to guess that this amusing little opera would become as it has a fixed planet, so to speak, in the world of wit and humour. In proof of this, witness the way it shone some short time since at Drury Lane in honour of Ellen Terry's jubilee of work. Quite a notable feature of this particular performance was the excellent restrained force displayed in the part of the Associate by the talented author of the libretto, who met with a reception at the hands of the vast audience which must have given him intense pleasure, as indicative of the delight felt at yet one more opportunity of manifesting the keen appreciation of the many hours of fun his work has furnished.

In saying that no one knew very much about Gilbert and Sullivan, I mean, of course, in their capacity as a "Firm," for all the world had been for long enjoying their work as individuals, the musical status of Sullivan being already established, while Gilbert, apart from plays he had written and slight pieces for the German Reeds, had already endeared himself to all lovers of humour with the famous "Bab Ballads"; but to my mind much of this was overlooked when they took us all by storm as "Gilbert and Sullivan." Say it aloud, and see how it runs off the tongue. Truly it was a musical firm. My goodness, how we all stood in awe of them at the early rehearsals of the Sorcerer! We had not had time to arrive at the kindly kernel concealed beneath the autocratic exterior of the partners. Not that the two together were then so autocratic as one of them became later on. And good reason they had too, for they dominated the musical market, and to get with Gilbert, Sullivan, and Carte was the one desire of every artist with or without a voice.

The great initial idea was that every soul and every thing connected with the venture should be English. It was to be a home of English talent, and so strong was this feeling that two choristers, whose names were never likely to appear on the programme, renounced their Italian titles and became Englishmen for the express purpose of being associated with such an enterprise; and one dear old fellow (he is still alive, though he seemed old even then) very nearly missed his engagement because his name was Parris. This sentiment inspired us all with a kind of patriotic glow combined with a determination to show other nations (and inter alia our own) what we could do; and I remember feeling great distress at the risk run by my old colleague Dick Temple, who would use the " Italian production," which unfortunately there was no mistaking. However, I was soothed by noticing that it gradually left him during the course of rehearsals.

I need hardly say how more than delighted I was with my part; I could not very well have a better one offered me to-day. But as the time of production drew near I began to feel rather anxious about it, and confessed as much one day to Gilbert, saying that I felt what a daring experiment it was to introduce a Dean into comic opera, and that I fancied the public would take either very kindly to me or absolutely hoot me off the stage for ever. He was very sympathetic, but his reply, "I quite agree with you," left me in a state of uncertainty.

There was a song in the second act demanding an obbligato on the flageolet, which Sullivan suggested should be played in the orchestra; but I demurred to that, and received permission to play it for myself. A part was written out for me, I learnt it (it was only two notes), and it added enormously to the success of the song.

The Opera Comique, though giving from the auditorium a sense of elegance and plenty of room, was in reality one of the most cramped theatres it has ever been my lot to play in. It was like a rabbit-warren for entrances, having three or four in as many different streets, and from the principal one, which was in the Strand, there was an excessively long and narrow tunnel to traverse before arriving at the stalls, which would have been an awful place in case of fire or any panic; fortunately the former never happened, and the latter only once, when it was speedily dissipated. With the exception of one or two little cabins, more resembling stoke-holes, below the level of the stage, occupied by the ladies and the tenor (I do not mean jointly, of course), all the dressing-rooms were upstairs, in houses along Holywell Street, commanding a fine view of the celebrated literary emporiums of those days, and reached from the stage by a flight of some thirty very steep stone steps, commencing almost at the street door. The back wall of the stage was also the back wall of that of the Globe Theatre; indeed, by placing the ear to any little crevice the players on either side could overhear the others.

George Grossmith, Richard Temple, Fred Clifton, and myself shared one not too large room, and George and I had to assert ourselves on one or two occasions in order to maintain an equality with the two older hands; but we were a very harmonious four for a long time, though there was nearly a split in the camp when Clifton insisted on supping in the dressing-room, our objection to which habit arose entirely through his inordinate predilection for sheep's head, possibly a very succulent dish, but a truly ghastly object to look at. I believe it was a supper much affected by "the old school," of which he was undoubtedly a very talented member.

At last we arrived at the first night, and though we all felt confident of success, we little dreamed how this evening was to be the precursor of all those historical first nights which remain without parallel in the annals of our stage. I believe we were none of us as nervous as we ought to have been, simply for the reason that we hardly appreciated the magnitude of our undertaking. I can only say that personally I have felt very much more anxious at later nights. What a rush there was on the part of the company for the next day's papers, and how eagerly they were scanned! Really there are few sensations much more pleasant than that of reading something nice about yourself in print. I do not mind admitting that it comes almost as fresh to me in 1908 as it did in 1877. I will confess to a certain feeling of disappointment at the dictum of one well-known critic of those days (whom later on I met and liked immensely), who said, " Barrington is perfectly wonderful. He always manages to sing about one-sixteenth of a tone flat; it's so like a vicar." As a matter of fact, he was so pleased with this criticism that he was constantly repeating it, with the ultimate result that I established a reputation for doing it, and many months later nearly got into trouble over it. Carte himself came round to see me in a great state of mind, saying, " B., what's the matter? " I had I visions of an ignominious dismissal for something, I did not know what, that I had done. " What is it, D'Oyly?" I said. "Why, some one has just come out of the stalls to tell me you are singing in tune. It will never do." This pleased me so much that I have never sung flat since, except, of course, when I wished, and in thus altering my method I unconsciously ruined an imitation of me which Charlie Hawtrey used to give, and which depended greatly on that sixteenth, though he was not particular to one.

I was much impressed with the thoughtfulness I displayed by an unimportant member of the company, I who would come nightly to inquire after the health of George Grossmith, and I told George how nice I thought it was of him. George quite agreed, but remarked parenthetically, "He's my understudy, you know, and he said he thought I was looking awfully I overworked and in need of a change." I still maintained that I thought it very considerate behaviour, but when, later on, he offered George his expenses to go away for a few days, I began to think he was not quite so disinterested.

I believe that George Grossmith's quaint run round 'the stage, brandishing the teapot in which he had mixed the love-charm, was an absolutely unrehearsed effect; but whether this was so or not, the success of it was undeniable, and I imagine started the series of similar antics in the parts which followed, and without which he would have seemed rather at a loss.

The Sorcerer was memorable to me for one very personal reason, being the first play my father had ever seen. He had the old-fashioned, much exaggerated ideas of the wickedness of "life in the green-room," and indeed carried his convictions to the extent of saying that if I appeared on the boards (they called it the boards then) before I was of age he would have me forcibly removed by the police. I do not know whether he could have done it, but waited the prescribed time, and the dear old man softened so rapidly that within two years he found himself in a theatre looking at his son acting; and most complimentary he was to me.

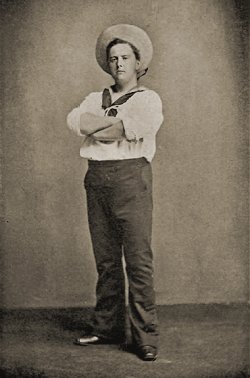

After about one year of the church I launched on a seafaring career as the captain of H.M.S. Pinafore, which first saw the light in 1878. Surely this is one of the most joyous and breezy plays ever seen or likely to be. It is almost a cure for depression to whistle the first bars of the opening chorus, with its lilt so redolent of the sea. It is perfectly unaccountable, and yet the fact, that this opera did not take hold half so readily as The Sorcerer had; indeed, not until it had been produced in America where our cousins went literally crazy over it, and the fame of it had travelled back to London, was il the success it eventually proved.

Jessie Bond made her first appearance in this opera as the leading relative of Sir Joseph Porter. She struck me at rehearsal as being of a rather stodgy, not over-intelligent type of girl, showing very few signs of the strong personality and great artistic capabilities that were to make her a firm favourite of the public within a short time. We had a change of tenor for this opera, Bentham being considered on too large a scale for Ralph Rackstraw, I believe, so that the new draft also included George Power, the possessor of a sweet if delicate voice, and a manner somewhat to match. He was suffering one night from a cold, and had played almost through the first act under difficulties when the finale came. It begins by Rackstraw rushing on to summon his friends with "Messmates ahoy!" Power's voice cracked very badly, and he immediately bolted off the stage, leaving the musical director with his baton in the air waiting for " Come here ! come here ! " Our stage manager, Barker, a good-hearted but grim-mannered fellow, rushed up to George Power, who said plaintively, " It's no use, Barker, you must send on the understudy." Barker's reply was to grab him by the collar and literally hurl him on to the stage, exclaiming, " Idiot! d'you think I keep the understudies in the wings on a leash? "

There was a wonderful performance of Pinafore given entirely by children, all of them taught by Barker, and it was beautiful to see how gentle this rough man could be and the pride he took in their efforts to please him. At the first performance I was standing beside him in the wings when the Middy bars the way to Josephine. Imagine the size of this Midshipman when all the others were children. The little mite did it splendidly, and Barker exclaimed in a tone of delight," Bless his little heart. I knew he'd do it, damn him! "I do not know what became of the majority of these clever children, but the juvenile lover made a certain success later as Henry Eversfield.

Among the many charming people associated with us at this time, there was no more genial and delightful personality than that of our musical director, dear, sweet-natured Alfred Cellier, the composer of many charming songs, some of which will live while music lives. He was also one of Sullivan's two closest friends, the other one being Frederic Clay, the same type of man and also a composer of note, as evidenced by the undying and deserved popularity of one song above all others, "I'll sing thee songs of Araby." To me, standing practically on the threshold of a new kind of existence, it was a source of intense gratification and delight to be treated en camarade by these two men, so distinguished in the world of art and so popular in that of Bohemia; and a Bohemia that I venture to think does not exist in these latter days, owing not only to the changed conditions, but also to the necessarily unwieldy proportions it assumes.

The only drawback to much association with Alfred Cellier lay in the somewhat upsetting manner he had of turning night into day, seldom putting in an appearance before lunch-time, and being abnormally wide awake when some of us were longing for bed. But in this respect he was no worse than another well-known man whom I was proud to call my friend, E. L. Blanchard (the " old boy " of so many Drury Lane pantomimes), to walk and talk with whom was an education, the lesson frequently ending at a most fascinating little club called the Arundel, which, if I remember rightly, only opened its hospitable doors at midnight, and where there was always a kettle of boiling water for hot grog on a tripod on the centre table in the room. I am not sure what time the club closed, but I have several times left it and gone straight home to breakfast; and there were no such things as fines in those days, such as are inflicted now if one stays in the club after three.

Apart from the licensed critic, many people used to say of me that it was little wonder I played the vicar well, as my father was in the Church; and when it came to the turn of Pinafore they discovered an identical line of reasoning in that I had a brother in the Navy. No allowance was made, either for the possibility of lurking talent or the bringing out thereof by the ablest stage-manager I have ever seen at work — Gilbert, to wit — oh dear no! But this line of argument failed a little later when we produced The Pirates of Penzance, in which I played a Sergeant of Police, as in spite of all efforts they could not unearth for me a relative in the Force.

There was a flutter of excitement all round the theatre one night when we found that H.R.H. the Prince of Wales had announced his intention of coming. Our first Royal visitor, and, to add lustre to the occasion, Sullivan was to personally conduct the opera. We all looked forward to a brilliant and delightful evening, and I believe we had it; in fact, I am sure we did, with one exception myself and it was absolutely spoilt for me. Whether it was that in the course of so many performances we had altered the tempo, or that Sullivan after so long an absence had forgotten what it should have been, will never be known, but the fact remains that he took the Captain's first song so slowly that it not only missed the usual encore, but absolutely went without a hand. I could have cried indeed, I believe I did and I had a terrible feeling that His Royal Highness would never forgive me. Of the rest of the evening I remember nothing. How human nature measures everything by a personal foot-rule !

Another exciting evening during this run came when we were playing as a front piece a charming little one-act opera, by James Albery, called The Spectre Knight, with some of Alfred Cellier's most delightful music in it, notably two quartettes which live in my memory to this day, and which I should love to hear again. Richard Temple was the Knight, and was also the Dick Deadeye in Pinafore, and as my dear old friend was always suffering from a kind of contempt for anything less majestic than what is known as English Opera (which generally consists of Italian Opera played in English, I fancy), he was always giving odd performances of different operas, in which he played the leading part.

He had arranged one of these for a Saturday night at the Alexandra Palace, and I could not understand how he meant to be in two places at once. However, he murmured mysteriously that "it would be all right"; but it was not, for on the night in question came a telegram from the Palace to say, "Unable find substitute, must remain here for Rigoletto." We had to keep the curtain down for the first piece as no one could wear the Knight's armour, and of course the understudy had to go on for Deadeye.

We all thought Temple would suffer nothing less than decapitation for this escapade, but he seems none the worse for it to this day; but in spite of his apparently escaping scot-free, I must admit that I should never have dared such a thing on my own account, and I feel sure he could not have given a good rendering of Rigoletto with such a crime on his mind. Temple was rather good-looking in those days (he has not altered much, I believe), and his make-up as Deadeye, one eye being blind, was exceedingly good. I remember a visitor to the dressing-room one night complimenting him on it, and remarking that "he should not have known him, it was quite a dead identity."

Page modified 4 September 2011