|

|

||||||

The Beauty Stone

From "The Illustrated Sporting and Dramatic News"

25 June 1898

The Savoy is, I think, suffering from its traditions. It has been consecrated, so to say, by a long period of the Gilbert- cum-Sullivan combination—has become so thoroughly associated in our minds with this particular form of entertainment—that we look askance at all and any modifications there. I am afraid that with every wish to be unbiased I cannot myself plead complete guiltlessness of this common fault of our play going nature, which must be my excuse if I am wrong in feeling that The Beauty Stone is not quite at home in Mr. D'Oyly Carte's charming little theatre.

It is not at all a badly written piece, either as regards the story or the music but it lacks the quaintness, the character, the life, of the familiar repertory and it is received with esteem only—not with enthusiasm. The plot, for all that, has freshness—coupled with something of boldness; the dialogue is neat; the lyrics are fanciful; and the personages have contrast. But on the other hand, the action is deliberate to tediousness occasionally—and there is absolutely no fun.

Much of the blame of this must, I fear, be attributed to the anxiety of the authors to be literary before all things, and this anxiety, which is especially obvious in the songs, seems to have taken something of his usual go out of the composer. Mr. Comyns Carr has studded the book with verses full of graces, but infinitely more suitable for an album than for the boards. He has crammed his elaborate lines with pretty conceits to which it would be extremely difficult for the musician to give detailed expression, and so Sir Arthur Sullivan's setting, while naturally it displays his unfailing talent, occupies, for the most part, a place midway between gaiety and emotion—or, should I say, between Gaiety and Covent Garden.

He is best where he is least tied to his libretto—in dance, march, and storm; but he is not so telling as he might be in the love episodes and passages of vocal comedy— largely I fancy owing to the lack of simplicity of the rhymes. Considering the amount of twaddle which does duty for verse in comic opera, it is hard that Mr. Comyns Carr's good work in The Beauty Stone could give us no more satisfactory result than this—many of the lyrics are really excellent poetry. But to write rhymes for the theatre like writing tales for children is a special gift. Mr. Carr is not the first poet who has proved it.

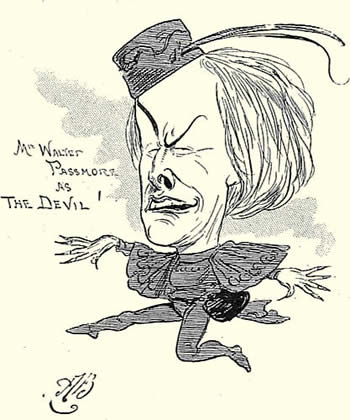

The central figure in the new Savoy piece is the devil. The authors say that he is the devil of the Mystery Play of the Middle Ages—a grotesque demon. This may well be so, and if we had not been spoilt for a demon of this kind by burlesque and pantomime the idea might have been effectively carried out. As it is, Satan represented by Mr. Passmore reminds us of nothing so much as of the Yellow Dwarf; and face to face with this evil one, who dances and skips about and cachinnates, and is not dignified—only fierce—even when exerting his influences supernatural. I must confess that I prefer my Mephistopheles, in a play like this of otherwise serious interest. For the idea of The Beauty Stone surely is of serious interest—so far as its not very strong interest goes. The stone is a talisman which the wicked one gives to a persecuted maiden, who is persecuted and contemned because she is a cripple. Its possession makes her lovely enough to attract the attention of the local baron, and to win his somewhat unstable affections from his mistress, whom he had picked up while a wanderer in the East. Indolent almost to lethargy, he refuses to be stirred into action, passing his time among pretty women and pretty things.

The heavenly graces of the heroine— though the endowment is more directly from the nether regions—come upon him with a charm which is irresistible, and at once he falls at her feet. She innocently confesses the admiration which, when a cripple, she felt for her fine-looking feudal seigneur, and apparently dreading no ill, consents to stay in his castle. But the treatment meted out to her humble parents and the lecture which a plain-speaking veteran delivers, without effect, to her luxurious, lazy admirer, opens her eyes. She talks to his lordship in turn, with even more vigorous denunciation, makes her escape from the castle and throws the beauty stone away. Her lover, much ashamed of himself, then goes to the wars. Her tattered father—his daughter a cripple once more—does not see why a good talisman should be wasted and, after first offering it to his tattered wife, avails himself of it for his own benefit, and becomes a handsome and respectably-clad young man. Encountering the Eastern lady—who wishes to secure the charm for her own purposes—he leaves his home in pursuit of her, and she temporises with him until she has robbed him of the magic gem. Her object is to be so young and so lovely when his lordship returns conquering, that all his old ardour will be revived. But, unfortunately, he returns physically blind—has lost his eyes during an assault, and can only see with his mind. He sees, through that medium, the purity and innocence and other graces of the despised cripple maiden, and amid general rejoicings makes her his wife. There is fair interest throughout the performance of this story, which alternates between rags and cloth of gold, but, as I have hinted, little heartiness in the reception. The encores are mainly for the dances, of which that of the demon and a wild young lady whom he picks up in the streets and converts into an attendant page, is more popular than harmonious to the subject of the play. Mr. Passmore is the demon, practically as I have described the part and Miss Owen shows vigour and comedy as the sprite, who for no reason except to be sent about her business, actually falls in love with his eccentric infernal majesty.

|

|

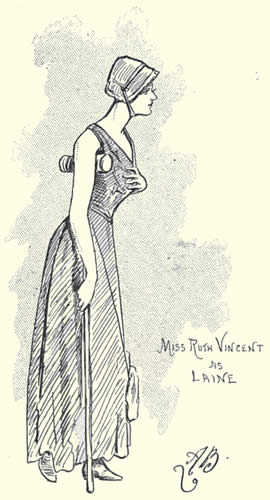

Miss Vincent, as the heroine, is able and sympathetic, and Miss Joran as the Eastern person is picturesque and dramatic. The male cast is not so strong as the female side. The Duke of Mr. Devoll looks duly indolent, but has not great force; the persistent veteran of Mr. Isham, the Simon, a struggling elderly weaver, afterwards a sentimental lover, of Mr. Lytton, and the Burgomaster of Mr. Hewson, are the other principal parts. Mention must also be made of Miss Brandram as the heroine's affectionate mother and Simon's forgiving wife. The piece is extremely well mounted. The scenery is admirably painted, and the dresses show imagination and a vast amount of richness and colour. As regards the better or more expensive portions of the house the production seems to be a fair success—a success which Mr. Carte deserves not only by his liberality but by his good intentions and by his efforts, blow fair or foul, to sail his ship by worthy methods only.

Page modified 12 November 2020